[As of 7.7.22] 80-Min Total Read Time.

Please note this is a non-revenue generating, personal blog and not a commercial endeavor. So, it has not been professionally edited and you may find typo’s and grammatical errors, never mind potential minor errors with dates, numbers and the like. Please feel free to let me know of any and I’ll fix them. The images and quoted material contained herein is, in many cases, from copyrighted sources, but is done so under the legal, Fair Use Doctrine.

Introduction & Overview

This past March I decided to re-direct my interests and writing energy to something more productive, essentially local history beginning with how Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park came to be in April, and by March was digging-into and writing A Chronological History of Marietta, Cobb County & The State of Georgia. And, earlier this month I created a virtual, photo-based walk around the Marietta Square, adjacent streets and a few other areas of interest that provides images of what Marietta looks like today, and back in time using historic photos entitled, Marietta, Georgia: A Photo Compilation of “Now & Then”.

However, it was impossible to study the history of Cobb County and Marietta without taking time to learn more about Air Force Plant 6 (originally Government Aircraft Plant 6) and Dobbins Air Reserve Base (originally Rickenbacker Field). The history of the airfield and plant is directly tied to several key individuals involved in local politics during the 1930’s, who successfully secured support and funding for both the airfield and the plant in the early 1940’s. The two, parallel programs brought much-needed, new work on two major construction and associated infrastructure projects, as well as a huge boost in the local economy and commerce from the thousands of men and women who built the airfield and plant, and then the tens-of-thousands of people who worked at the Bell Aircraft Corporation leased and operated plant during World War II, from 1943 through 1945.

Perhaps even more important has been the subsequent, re-opening of Air Force Plant 6 in 1951 by the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. Unlike its first life that only created a three-year injection of economic growth and prosperity to the local community, under what is now the Lockheed Martin Corporation’s Aeronautics business area’s site at Air Force Plant 6 in Marietta, Georgia, the plant has remained in continuous operation for 71-years and been an important part and partner to Cobb County and the City of Marietta for all of those years.

Having worked at Lockheed from 1984 through 2018, and at the Marietta plant from 1991 until I retired in 2018, I knew quite a bit about the history of the F-22 and C-130, as they were both programs I worked-on in a program management capacity. However, once I started to dig-into the history of the plant, I realized just how much I didn’t know or appreciate about it, or even many of the aircraft that were produced at Air Force Plant 6 by both Bell and Lockheed.

Therefore, this is the product of that research, something I took on as a personal project in my spare time over the course of the past two-weeks, and as a follow-on to the aforementioned virtual, photo-based walk around Marietta, Georgia using historic photos. My goal was to try and capture in an internet-enabled, visual history trip with historic photos from the past, some married with more current images of the same places and buildings, to create an interesting, enjoyable and attention-holding retrospective on “The Bell Bomber Plant” as it’s always been known. And, it was hard to not include information regarding the amazing aircraft built at the plant since 1943 by tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people who have worked at the plant over all of those years, and who might want to either revisit the history they helped create, or learn the history they never knew.

The format I’ve used is intended to be both read and viewed, as there is a lot of written material here — 26976 words — but also a lot of images — over 350 — I’ve tried to arrange in subject-specific collections that have their own story to tell. Therefore, the history I’ve compiled can be read and viewed in part or its entirety, or simply looked-through using the images to tell the story, as most have detailed descriptions that explain what viewers are seeing. I’ve also included a hyper-linked index so readers can jump to sections or subjects that are of most interest, eliminating the need to scroll through all of the words and images to find the content that’s most interesting to them.

So, with that, here is my retrospective, chronology and image-based history trip.

Index of Featured Areas / Photos: Click on Links to Jump to Section

- A Chronological Recap of the Origins of Marietta Airfield & Government Aircraft Plant 6

- James V. Carmichael, Rickenbacker Field & Government Aircraft Plant 6

- Lockheed Reopens Air Force Plant 6 in the 1950s & Dan Haughton

- Timeline for Marietta Army Airfield and Government Aircraft Plant 6

- Resources: More about the Bell Bomber Plant History (Video)

- Construction: Building Government Aircraft Plant 6 & Big Lake Dam

- The Finished Factory: 1943 vs 2022 Aerial Views

- Marietta Army Airfield: Timing’s Everything

- Government Aircraft Plant 6: Five Buildings & 4.2 Million Square Feet

- Building B-2: Administration

- Building B-1: Main Assembly

- Buildings B4, B3 and B-6

- Parking Lots, Streetcars & South Cobb Drive

- Other Buildings & Features

- The Marietta Army Airfield’s Officers Club & Lockheed Proposal Center

- Other Related Developments

- The Product: The B-29 Superfortress (Video)

- The Early Lockheed Years: Air Force Plant 6 Gains a New Lease on Life

- Lockheed’s Airlift Legacy – Beyond the B-29 Refurbishment Program

- A Brief Introduction & Lockheed History

- It’s Not Been All Sunshine & Roses

- The Boeing Designed, Georgia Division-Built B-47 Stratojets (Videos)

- The Lockheed YC-130 / C-130 / L-100 Hercules Program (Video)

- The YC-130 Program Chronology

- The Full-Scale Model & Hydrostatic Testing

- The First Articles & First Flights

- The First Lady & Fire on Number 2

- The C-130A Is No Trash Hauler

- A Plane for All Reasons & Missions

- The L-100 Commercial Variants

- The C-130J Variants in Production

- The Embraer C-390, The First Serious Alternative

- The Skunk Works Designed, Georgia Built JetStar Business Jet(Video)

- Development of the L-329 JetStar

- An Iconic Aircraft In It’s own Right

- The Georgia Designed & Built L-300 / C-141 Starlifter Airlifter(Videos)

- The USAF Requirements & Lockheed’s Design

- Initial Production

- The C-141 “Bulked-Out” & Gets Stretched

- C-141 Finishes & Paint Schemes

- The SOLL II, C-141 “AMP” & Replacement by C-17

- Other Milestones & Resources

- The Georgia Designed & Built L-500 / C-5 Galaxy Airlifter(Videos)

- The Proposed Designs & Cost-Based Decision Making

- The Cathouse and The C-5 Flight Test Center, L-10

- The 1st C-5 Falls Victim to a Fuel Fire

- First Flights & Different Paint Schemes

- C-5 Size Comparisons

- The C-5B, C-5C, AMP & RERP and C-5M Designation

- Retirement of the C-5As & the Success of the C-5M

- The Technical Marvel was not a Financial Success

- The Airlift Years & Aircraft – What’s Next?

- History Simply Repeats Itself

- F-22 Migration & Closure of the Burbank Plant

- YF-22 Moves to Georgia Ahead of F-22 Contract Award

- General Dynamics Fort Worth & Martin Mergers

- The Joint Strike Fighter Enters the Mix

- F-35 Wins JSF & Headquarters Moves to Fort Worth

- End of F-22 Production & Marietta Becomes a Site

- Skunk Works Expansion & Migration to Georgia Begins

- History Simply Repeats Itself

A Chronological Recap of the Origins of Marietta Airfield & Government Aircraft Plant 6

During 1933 – 1940, attorney James V. Carmichael, born and raised in Cobb County, Georgia, forms a legal practice with future Marietta Mayor Leon “Rip” Blair. He also runs unopposed and serves two-terms in the Georgia legislature, establishing himself as a key member of the Cobb County business and political community.

In 1940, Carmichael, then the Cobb County Attorney, his legal partner and now Marietta Mayor Blair, as well as former Cobb County Sheriff and then Cobb County Commissioner, George McMillan teamed-up to gain support from Marietta native and then U.S. Army Air Corps Major Lucius Clay, for a new airfield in Marietta.

- Major Clay was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in September to head up the Civil Aviation Administration’s (CAA) expansion of U.S. airfields as the U.S. prepared for potentially going to war.

- Carmichael’s group successfully secured support, government approval and CAA funding to establish and build a civil airfield at Marietta, initially to be called Rickenbacker Field. The approved plan to build the airfield was announced in October 1940.

In 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into World War II, Carmichael’s group leveraged the recently approved, future airfield and secured the government’s acquisition of additional land and construction of Government Aircraft Plant 6 at Marietta, to be used for co-production of Boeing B-29 Superfortresses by the Bell Aircraft Corporation.

- The selection of Marietta for Government Aircraft Plant 6 was announced on 19 February, and construction of the Government Aircraft Plant 6, as well as what would now be Marietta Army Airfield, both began in March, with ground-breaking at the Government Aircraft Plant on 30 March 1942. Although construction began at what would now be Marietta Army Airfield in 1942, its official ground-breaking ceremony took place in May 1942, with Captain Rickenbacker present.

Also in 1942, Bell Aircraft Corporation CEO, Larry Bell, appointed Carmichael who was just in his early 30’s at the time as chief legal counsel for Bell’s Georgia Division. He would later be named as Bell Aircraft’s Georgia Division vice president and general manager in 1944.

In 1943, Government Aircraft Plant 6 was completed on 15 April, and the renamed Marietta Army Airfield was completed on 6 June.

In 1945, following Japans surrender in August, production of B-29s at Government Aircraft Plant 6 and the Bell Georgia Division was halted in September, with surplus materials being dispositioned and residual tooling and equipment stored in Building B-1.

Timeline for Marietta Army Airfield and Government Aircraft Plant 6

Resources: More about the Bell Bomber Plant History

For those who don’t have a lot of time to read this blog, or who prefer to get their information via video, the following image is linked to a movie produced by Bell Aircraft in 1944 that provides a good overview of the Bell Bomber Plant history and many of the things covered in my photo collection and comments.

The following are great resources for the full history of the Bell Bomber Plant and Government Aircraft Plant 6, built back in 1942 and 1943 when Bell Aircraft Corporation produced 668 B-29 Superfortress bombers under license from the Boeing Aircraft Corporation. And, in so doing, gave an immediate infusion of much needed life to the city of Marietta and Cobb County, which were still trying to gain their footing following the Great Depression of the 1930’s that had been exceptionally hard on small communities in the south.

- Fandom: Military Wiki

- The New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Georgia Public Broadcasting “This Day in History“

- Wikipedia

- “The Lockheed Plant” by Joe Kirby

- The Atlanta History Center Photo Collection

- Kennesaw State University Photo Collection

- Kennesaw State University Teacher’s Guide

Construction: Building Government Aircraft Plant 6

The 1906 Big Lake Dam at Fourth Street

As an interesting bit of local history, the Big Lake Dam that had supplied water to businesses in Marietta from 1906 until the 1920’s was, and still is on Dobbins Air Reserve Base property, not Air Force Plant 6. However, given the Rickenbacker / Marietta Army Airfield project was directly associated with the creation of Air Force Plant 6, I’ve decided to include the mention and photos.

This was something I discovered through Facebook postings on a personal FB page that’s since been commercialized. The discovery was somewhat surprising, as having worked at Air Force Plant 6 in different roles that enabled me to cover a lot of ground at both the plant and Dobbins, I did not know this particular “lake’s” tie-in with Marietta, or the background of the dam. It’s somewhat hidden, just south of Atlantic Avenue on 4th Street at the Dobbins ITT/Landing and Recreation Area, has a fascinating history, and is just southeast of where the Jonesville Cemetery is located.

The dam and reservoir operated for less than 20 years and only provided water to the city of Marietta for about three years. The standpipes, pumps, underground pipes, associated machinery, and plant in Marietta no longer survive. Big Lake Dam and Big Lake are a rare example in Georgia of a fairly large-scale water impoundment facility constructed for a small municipality.“

Site Work

Excavating & Creating the Sub-Level & Tunnels

Enclosing 3.2 million square feet

The wood block flooring helped to prevent back problems among workers who spent prolonged hours standing at their work stations, and also allowed for easier relocation and movement of equipment. It was a standard feature on all of the Government Aircraft Plants built during the 1940‘s, e.g., Government Aircraft Plant 1 at Offutt AFB, Nebraska (the Glenn Martin Plant), Government Aircraft Plant 2 at Fairfax Airfield near Kansas City, Kansas (the North American Aviation Plant), Government Aircraft Plant 3 at Tulsa, Oklahoma (the Douglas Aircraft Plant), Government Aircraft Plant 4 at Carswell AFB, Texas (the Consolidated Aircraft Plant & now headquarters for Lockheed Martin Aeronautics), Government Aircraft Plant 5 at Tinker AFB near Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (also a Douglas Aircraft Plant), and many others.

The Finished Factory: 1943 vs 2022 Aerial Views

Marietta Army Airfield: Timing’s Everything

For those who don’t know the full history of Dobbins Air Force Base and the runway it shares with Air Force Plant 6, it too is somewhat interesting. When Bell and then Lockheed were leasing Air Force Plant 6 to support exclusively U.S. government contracts associated with building or refurbishing the B-29 and, later, the B-47 and C-130 aircraft, it seemed to make sense since there was a purely government propriety to the partnership. However, since the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, when the Georgia Division of Lockheed Aircraft Corporation began to produce commercial aircraft at the Marietta plant, first with the L-329 and L-1329 JetStar executive aircraft, and then the L-100 commercial variant of the C-130, the lawyers and accountants had to sort it all out in dual-use agreements. But I digress…

A very detailed history of what is now Dobbins Air Reserve Base can be found on Wikipedia that’s worth a read, as it’s quite revealing with regard to how political and economic leverage play into government investment and development of installations. In fact, a total of 85 different types of “Air Force Plants” were established since the first, Government Aircraft Plant 1 at Offutt Air Field in 1940, which also required the construction of both the Glenn L. Martin bomber plant and a runway.

However, getting back to Government Aircraft Plant 6, in September 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt tapped U.S Army Air Corps General Lucius Clay to head an emergency airport-construction program, under the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA), to prepare the country for possible war. Over the next fifteen months, General Clay shaped plans for construction of over 450 new airstrips, including one in Marietta that was envisioned as handling overflow of commercial traffic for Atlanta’s Candler field but, local officials who were close to General Clay, were clearly aware of the potential for the field to convert to military use in the event of war.

In less than a month after General Clay assumed his role, the CAA offered to fund and build the airport in Cobb County if the local governments provided the land, and by the end of October 1940, Cobb County announced the airport project. By May 1941, Cobb County issued bonds to purchase 563 acres along the new four-lane U.S. Highway 41, linking Marietta with Atlanta, and the CAA allocated $400,000 for construction of two 4,000-foot (1,200 m)-long runways. The bid for construction of the runways was well-below the government’s estimated and budgeted cost and allowed the CAA to add a third runway to the project. Surveying, detailed planning and site work began on 14 July 1941, and in August Gulf Oil Corporation and Georgia Air Services agreed to lease the airport, once completed, for $12,000 per year. In September 1941, retired Army Air Corp Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, then the president and general manager of Eastern Airlines, agreed to have this airport named Rickenbacker Field in his honor, and the U.S. Navy requested permission to use this airport for the flight training of Naval aviators. In October, Georgia Air Services signed a $70,000 contract for two 180×160-ft. airplane hangars to be built. Although far from complete, the airfield was dedicated in October 1941.

On January 23, 1942, the Bell Aircraft Company and the Department of War announced an aircraft factory employing up to 40,000 workers would be built near Marietta. On February 19th, a subsequent announcement advised “Rickenbacker Field” would be renamed the Marietta Army Airfield, with the CAA-funded runway construction beginning in March 1942, its official ground-breaking ceremony took place in May 1942, with Captain Rickenbacker present. The Marietta Army Airfield was activated on June 6, 1943, with the assigned mission of conducting acceptance testing of B-29 Superfortress’ produced by the Bell Aircraft Company at Government Aircraft Plant 6.

The airfield was renamed Dobbins Air Force Base in 1950, in honor of a local Marietta aviator who lost his life in World War II. In 1955, the U.S. Navy finally firmed-up plans to establish a Naval Air Station at Marietta Army Airfield and Congress appropriated $4-million dollars to fund the lengthening of the runways to meet their needs, remembering the original, three runways cost only $400,000 in 1941. In 1957, Naval Air Station Atlanta at the present-day Peachtree-DeKalb Airport, was relocated to new facilities on land southwest and adjacent to the Dobbins AFB runway, and the runway expansion was completed in 1959.

Government Aircraft Plant 6: Five Buildings & 4.2 Million Square Feet

Building B-2: Administration

Building B-1: Main Assembly

With regard to its size, from Jeffery Holland’s book, Under One Roof – The Story of Air Force Plant 6:

The 3.2-million square foot B-1 main assembly building was designed with two parallel final assembly lines, each a half-mile long. It is 20,000 feet long, by 1,024 feet wide and 45 feet (four-and-a-half stories) tall with widely-spaced interior supports due to the wingspan of the B-29 bombers.

Construction of the steel superstructure began on September 1, 1942, and ultimately some 43 acres of concrete and 28,000 tons of steel were used. To address the risk associated with a potential, nighttime air raid, B-1 was a “blackout” facility with no windows so work could proceed 24 hours a day. The latter, in part, was made possible since the building was air-conditioned, a rarity in the South at that time. The air-condition was also needed to keep the building’s temperature constant to prevent metal material and components from expanding, contracting or warping. The ventilation system moved 4 million cubic feet of air per minute through the plant and, while the tunnels and basement were not air conditioned, 14 ventilators were used to circulate the cooler factory air through the lower levels of building B-1. Aa separate ventilation system in the building’s also indoor, blacked-out railroad bay & freight platforms that ensured smoke and dust from trains and off-loading of materials was kept out of the factory.

In terms of its size, some of the more common analogies used when it was built included: The B-1 building contained sufficient railroad tracks beneath its roof to have sheltered a dozen passenger trains. It was the equivalent of 63 football fields in dimension. And, it had room for 20 battleships, 69 submarines and 24 PT boats.

As noted above, building B-1 included a railroad bay used to support the delivery of parts and materials at a time when most freight movements were heavily supported by rail, and switching engines were operated by the plant.

Switching engines were used well into the latter part of the 1990’s as rail cars routinely transported C-5 and C-130 empennage parts in support of the Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Air Force Plant 6 production lines. In the past, several rail cars delivered large autoclaves for the B-1 sub-contract work and even an Abrams M-1 tank for the Georgia Tech research facility.

The last of the Baldwin switch engines at Air Force Plant 6, #1248, was retired in December 2016, originally built in the early 1950’s. It was surplused to Kirby Family Farm near Williston, Florida… a facility that provides educational, historical, recreational, agricultural, and community enrichment programs for at-risk and special needs children.

The tunnels were also used for vehicles, shuttling materials to and from the under-ground work area to the factory floor via three massive freight elevators at Tunnels 2, 3 and 4, but only the Tunnel 3 freight elevator went to the two upper floors of the central mezzanine complex inside of building B-1. The tunnel system also served as a bomb shelter for employees working in the main assembly and adjacent buildings.

Buildings B-4, B-3 & B-6

Parking Lots, Streetcar Service & South Cobb Drive

The lower left and center photos appear to be of the cars parked to the west of the B-1 parking lot at the construction management building and eventual 1940’s employment offices, and to the east of the Aviation History & Technology Center: Marietta Aviation History / old T-400 parking lot. This was likely, before the B-1 building was finished, as the B-1 parking lot appears to be empty.

That said, parking was always a problem in the early days of the plant, with nearly 28,000 people working at Government Aircraft Plant 6 at its peak levels during World War II.

The highly efficient streetcar service that existed during World War II was discontinued after the war, so parking became even a bigger problem following the plant’s re-activation for the Korean conflict and during the 1970’s and 1980’s with the C-130, C-141, and C-5A & C-5B production programs when employment reached nearly 33,000.

Reference the photo at right, if you look closely you’ll an observation tower at the northeast corner of the B-1 parking lot, near the intersection of Gibbs and Tinker Street with Blackjack Mountain in the background that was used to provide security surveillance of the massive parking lot, similar to how the portable units are now used by the Marietta and Cobb County Police Departments during special events or other places when appropriate.

Other Buildings & Features

To the east of the main plant was Building T-400, built as a “Temporary” structure (hence the T) in the 1940’s. It was still in use for the employment offices, personnel functions and several other administrative functions into the 1990’s but has has since been razed. The land and parking lot is now home to the Marietta Aviation History & Technology Center.

The north end of the Building B-4 Test Center is where the Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Fire Department had been located since the plant first opened, which was eventually where the industrial & plant security management offices were co-located in the 1990’s after building B-6 was condemned and eventually razed. I have no idea where those functions are now located, as I suspect both the fire protection and security functions had outgrown that building and there is no visible firefighting apparatus parked in the area in recent satellite images.

The Marietta Army Airfield’s Officers Club & Lockheed Proposal Center

Prior to being included in the eniment domain / condemnation of the Sibley farm on which parts of Government Aircraft Plant 6 was built, was the the Gardner-Sibley Home built well before the Civil War on the hilltop overlooking Atlanta Road and the Western & Atlanta Railroad, just west of building B-1. Known as “Cottage Hill,” noting many of the grand old homes in the south were given names and at a time when Marietta was considered a resort town where the southern elite congregated to spend leisurely summer evenings, even during the Civil War when it was far removed from the front lines of the war between the states. The home was purportedly battle scarred by the war as the Battle for Atlanta moved through Marietta and the Union Army occupied the city for several months before moving on and, in their wake, burning all the public buildings and any other structures that could be used to help the Confederate war effort, but otherwise spared from destruction.

The property would stay in the Sibley family until 1941, when the land was obtained through the eminent domain process and condemned along with several other homes and the community of Jonesville, to make way for the Marietta Army Airfield and Government Aircraft Plant 6 . When Government Aircraft Plant 6 was built and in operation during World War II, the home was converted for use as the Airfield’s Officers Club and Mess. After the new Dobbins Air Force Base Officers Club was built, the home and former officers club was used by Lockheed for business meetings and as a proposal development center. Sadly, it was allowed to fall into disrepair, was abandoned and eventually razed in 2015 and is now a vacant, hilltop lot.

A history of Josiah Sibley at the “Old Marietta (O.M.)” Facebook Page

Other Related Developments

The Lanham Act, Marietta Place & Public Housing

Housing was a pressing issue for Marietta throughout the 1930’s and into the 1940’s due to the Great Depression and assocaited economic downturns that took a heavy toll on Marietta. Many old neighborhoods near the Marietta Square devolved into slums that were in need of redevelopment and qualified for public housing, such that Marietta established a Housing Authority and applied for federal aid.

The first two Marietta Housing Authority projects for the City of Marietta were established just east of the Marietta Square. A 132-home public housing project called Clay Homes was built in 1940 to deal with the “slums” that had developed on the southeast side of the Marietta Square in the Hollandtown community for the white poor of Marietta, a separate, 120-home public housing project called Fort Hill Homes was also built in 1940 to replace the slums on the northwest side of the Marietta Square for the black poor of Marietta, remembering the U.S. south was still mostly segreated in the 1940’s.

Both projects have since been razed as of 2012 and recently replaced by upscale, $500k – $900k townhomes and single-family city homes. (Pulled from my article Marietta, Georgia: A Photo Compilation of “Now & Then”)

Housing was a pressing issue for many of the employees at Bell who had commuted from Atlanta or outlying areas sought more convenient housing near the plant, so the public housing plans already being developed by the Marietta Housing Authority were greatly expanded, such that before the plant was

completed, projects were under way for the development of over 2,000 housing units in Marietta. An October 1943 special “Bombers for Victory” edition of the Cobb County Times featured advertisements for a number of new apartments and housing developments in and around Marietta.

One of the largest of these was Marietta Place, located primarily to the southeast of the intersection of Fairground and Clay streets. Five hundred units were built by Hardin & Ramsey, an Atlanta contracting company under contract to Marietta Housing Authority. The single-story apartments were typically one-bedroom units grouped in four- to eight-unit buildings.

Another one of the more upscale project was Westpark, “The Subdivision in the Trees,” located northwest of the plant, and adjacent to the Marietta Country Club. The single-family homes featured Westinghouse electric ranges, Cold Spot refrigerators, and built-in cabinets. Unlike some of the “cookie cutter” housing projects for Bell workers, the Westpark developers touted the “variation of architectural design and landscape planting.”

Larry Bell Park

South Cobb Drive / Georgia State Route 280

From my, Chronological History of Marietta, Cobb County & The State of Georgia and a Cobb County Courier article entitled, “Road and Bombers: The creation of South Cobb Drive.”

One of the more unusual roads in Cobb County is South Cobb Drive, Georgia State Route 280 (GA-280), and its creation is directly tied to the Bell Bomber Plant in Marietta.

Following the announcement that Marietta had been chosen as the location for the new “bomber plant” over potential sites in East Point and Stone Mountain in a competition for the plant, Georgia’s Department of Transportation determined the main road between Marietta and Atlanta, the Atlanta – Marietta Road, was inadequate for expected volume of traffic that would be needed to transport workers and goods between Atlanta and the main railroad “hump yard” at Inman in northwest Atlanta and the Government Aircraft Plant 6.

The 12-mile road was originally called “the new Marietta Highway” and completed in the summer of 1943, leading from Bolton Road in Atlanta across the Chattahoochee River, skirting Smyrna and Fair Oaks, and connecting to the old Atlanta-Marietta Road, about one fourth mile from the Marietta city limit. At that point, it turned east and then south, heading to the entry gates at the Bell plant and then on to the “four lane” U.S. 41, giving it the distinct shepherd’s crook turn at its north end.

So, while it has become an important transportation corridor and commercial highway for dozens of communities in Cobb County, GA-280 was originally built as a single-purpose road, to connect Atlanta with a wartime bomber factory. It was subsequently extended at both ends and now links Interstates 20 and 75.

The Product: The B-29 Superfortress

A movie that appears to have been made at Government Aircraft Plant 6 in Marietta, Georgia, leased and operated by the Bell Aircraft Corporation that provides a very good overview of the B-29 fabrication process can be found on Facebook that I’ve linked to the following title shot image. Just click on the image and the Facebook video will launch, however, you may need to un-mute the audio.

The Photo Compilation Continues

However, if there’s one thing I’ve learned while doing research on this project, the five Government Aircraft Plants producing the B-29 at Washington state, Kansas, Nebraska and Georgia were all built around the same time using the same effort, materials and designs and look about the same. So, with few exceptions, any of these production line photos could have been taken in any one of the five plants unless you want to spend a lot of time studying the photos to identify something that clearly suggests which plant it was.

Bell P-39 Aerocobras were used as chase planes. It is interesting that one of the two Bell XP-77 prototypes, a simplified “lightweight” fighter aircraft using non-strategic materials, was at the Bell Bomber plant long enough to have photos taken alongside one of the Bell-built B-29 Superfortresses.

Also take note that the four B-29’s on the Northeast Parking Ramp are B-29B models without upper or lower fuselage gun turrets, just the rear, radar-operated tail gun. The latter change was made on 311 Bell-produced B-29B models as data analysis had showed nearly all fighter attack risks during World War II were from the aft. Eliminating the other four turrets provided a significant weight savings and simplified production and maintenance without significant increased risk given the mission profiles they were using in the Pacific Theater and fighter defense threat.

Size Comparison of the B-29 Bomber and the C-130 Transport

Just to add a little context to both the size of building B-1’s main assembly floor, above are two dimensioned drawings of the B-29 and C-130 in roughly the same scale. The B-29 has a wingspan of 141.3 feet, is 99 feet long and 22.4 feet tall. The C-130 has a wingspan of 132.5 feet, is 98.7 feet long (114 feet for the C-130-30) and 38.5 feet tall. To put the C-130 into context, I’ve added the illustration at right and below, along side some other well-known aircraft.

The B-29 Superfortress: A Complex, Large Aircraft & Production Program

Fabricating and assembling the B-29 was complex and was performed at five main-assembly factories. There were Boeing leased and operated Government Aircraft Plants at Renton & Seattle, Washington and another in Wichita, Kansas, the Bell plant at Marietta, Georgia, and a Martin plant at Omaha, Nebraska with literally thousands of subcontractors. A total of 3,970 B-29s were built & delivered to the U.S. Army Air Corps.

The XB-29 prototype made its maiden flight at Boeing in Seattle on 21 September 1942, and was plagued by setbacks caused by many factors. The YB-29, second prototype was fitted with a Sperry defensive armament system using remote-controlled gun turrets sighted by periscopes, and first flew on 30 December 1942. On 18 February 1943, the second prototype, which had been having engine system issues, experienced an engine fire and crashed, killing the 10-man crew and 21 people on the ground.

By the end of 1943, given all of the issues and needed design changes, although almost 100 B-29s had been delivered, only 15 were airworthy. General Hap Arnold personally intervened to address the problem that resulted in 150 aircraft being modified in the five weeks between 10 March and 15 April 1944. The most common cause of maintenance headaches and catastrophic failures was the engines that plagued the B-29 until after the war was over.

The B-29 was never deployed to the European theater for a variety of reasons and only saw use in the Pacific. From a practical perspective, the huge amount of space taken up by individual B-29s would have severely constrained the number of aircraft that could have been based at most British airfields, and the lack of long-range escort fighters in the European theater would have hampered B-29 operations, as much or more than it did those of B-17s. So, while the U.S. Allied Forced would have been able to attack German & Axis targets with more bombs per aircraft while putting far fewer crewmembers at risk, the production issues delayed B-29 introduction to the fleet until European Theater use became secondary.

However, In the Pacific theater, the distances to be covered essentially mandated the use of the B-29’s with their significantly longer-range than B-17s. And, again, the B-29 would have been of little use in Europe by the time they were finally being produced in numbers sufficient to support operational units.

The variants of the B-29 were outwardly similar in appearance, but were built around different wing center sections that affected the wingspan dimensions. For example, the wing of the Boeing / Renton-built B-29A-BN used a different subassembly process and was a foot longer in span than the other four factory-produced B-29S. The Bell / Georgia-built B-29B-BA weighed less through armament reduction.

With regard to the last 311 of 668 Georgia-built B-29Bs, in early 1945, Major General Curtis Lemay –-commander of the Marianas-based B-29-equipped bombing force—ordered most of the defensive armament and remote-controlled sighting equipment removed from the B-29A and Bs under his command. This gave the aircraft reduced defensive firepower, but an increase in range and bomb loads, which was ideal for the change in missions from high-altitude, daylight bombing with high explosives to low-altitude night raids using incendiary bombs. Based on this change, Bell’s Marietta plant produced 311 B-29Bs beginning in February 1945 that had turrets and sighting equipment omitted, except for the tail position, which was fitted with AN/APG-15 fire-control radar. This was the 3rd generation of defensive armament for the B-29, the first being more-like the B-17, the second a more advanced remote, streamlined turret system and then tail gun only, as show in the five upper right photos.

Similar to changes in the defensive armament, the first B-29s exterior finish was changed over time. Initially, B-29As were given the same olive drab painted-on finish as the B-17s operating in Europe. However, that was quickly changed to leaving them unpainted in their natural aluminum finish once it was realized they’d never be used in Europe and, instead, operate primarily over the Pacific Ocean where the dark-colored aircraft would be easier to spot than the dull grey of their aluminum surface panels. However, when the employment tactics were changed to night raids, the bright silver-grey aircraft became easier to spot against the dark skies, the lower half of the aircraft were painted black as a form of camouflage, something the Bell-Marietta factory began to use on it’s reduced armament B-29Bs. For some missions flown by certain units flying only nighttime missions, the black camouflage was extended to the entire empennage and tail section, as shown on a B-29B operating during the Korean conflict (bottom photo from above right).

The End of B-29 Production in Marietta

At its height in February 1945, Bell Bomber reached its peak employment of 28,158. About nine in ten employees were southerners, with the vast majority coming from communities in north Georgia. Some 37% were women, 8% black, and 6% physically disabled. Opportunities for advancement were limited for women and blacks, and the job sites were segregated. Yet, Bell’s equal-opportunity record was no worse than other southern industries of that era, and its pay scale was substantially higher.

By mid-1945 the plant began scaling back production and workers in preparation for the end of the war. As soon as the Japanese surrendered in August 1945, contracts for production of war materials were cancelled, including the on-going production of the B-29 Superfortress bombers at the Boeing plants in Washington & Kansas, the Martin plant in Nebraska, and the Bell plant in Georgia. Production of already in-work B-29Bs ended in mid-September 1945 when the last plane rolled off the line. By the end of September, the Georgia Division was down to a few thousand workers.

The local economy slowed slightly after the plant closed, but Marietta avoided serious unemployment, and the percentage of occupied houses and apartments remained high. The government used the B-1 main assembly building to store machine tools, and the Veterans Administration and other agencies took over the B-2 building.

The population of Cobb County reached 62,000 by 1950, up more than 60 percent from the total a decade earlier. In that year, the United States found itself in an undeclared war in Korea, and in January 1951 the air force invited the Lockheed Corporation to reopen the plant, with its first task being the refurbishment of B-29s for the conflict. What Bell had started, Lockheed continued… turning a formerly sleepy county into one of the most rapidly growing industrial communities in the country. In fact, Lockheed remained one of the largest employers in Georgia, Cobb County and Marietta up and until the end of the C-5 program, by which time government had become the largest employer in all three.

The Lockheed Years: Air Force Plant 6 Gets a New Lease on Life

1951 Plant Re-Activation to Refurbish B-29’s for Korean Conflict

During the latter part of 1950, as already noted, the U.S. Air Force invited the Lockheed Corporation to reopen and Government Aircraft Plant 6, just recently re-named Air Force Plant 6 at Marietta, Georgia, for the purpose of refurbishing and upgrading Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers that had been in storage since the end of World War II, as well as the potential co-production of Boeing B-47 Stratojet bombers as war broke-out in Korea during June.

4 January 1951, Lockheed accepted the Air Force’s invitation to re-open Air Force Plant 6 at Marietta, Georgia and appointed James Carmichael, vice president and general manager, who takes a two-year leave of absence from his post-war leadership role as president of the Scripto Company.

- Daniel J. Haughton, an Alabama native who had risen into the top management of Lockheed Corporation in Burbank, California, is appointed Carmichael’s assistant general manager and relocates to Georgia.

- In 1952, Haughton succeeded Carmichael as vice president and general manager of the Lockheed Georgia Division until 1956, when Haughton was named Lockheed Aircraft Company executive vice president, with authority over all operating divisions and subsidiaries.

- In 1961, Haughton succeeded Courtland S. Gross as president of the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, and in 1967 also succeeded Gross as chairman and chief executive officer.

The following headline appeared in the New York Times on 4 January 1951, and signaled the beginning of a new chapter in the Air Force Plant 6, Marietta and Cobb County history:

ATLANTA, Ga., Jan. 4–The former Bell Aircraft plant at Marietta, Ga., which cost an estimated $73,000,000 and turned out nearly 700 B-29’s in World War II, will be reopened by the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation at the request of the United States Air Force.

Again, Lockheed accepted the invitation and was put under contract to re-activate Air Force Plant 6 to support the refurbishment of 120 B-29 bombers produced and operated by the Army Air Corps during WWII, which subsequently became the United States Air Force in 1947. Beginning in the spring of 1951, Lockheed pilot Joe Gabriel and others began to ferry the 120 stored bombers to Marietta that had been “cocooned” to seal out the elements, and otherwise kept in flyable, reserve storage at Pyote Air Force Base, Texas,

Why Lockheed?

The Lockheed Aircraft Corporation based in Burbank, California, collaborated-well with rival manufacturers Boeing and Douglas in building the B-17 Flying Fortress during World War II, establishing a model for cooperative, licensed co-production. In early 1951, Lockheed had also put on contract to develop a master plan for converting the Palmdale Army Airfield into a Government Owned / Contractor Leased and Operated (GOCO) facility that would meet the requirements of full war mobilization and augment the industrial production potential of the major airframe manufacturing industry in southern California. To the current Air Force leadership, this positioned Lockheed as the ideal company to reopen the Marietta plant, as its initial tasks would be refurbishing Boeing B-29s and co-production of Boeing-designed B-47 bombers.

The first general manager of the Lockheed Aircraft Corporations newly created Georgia division was Cobb County native son James V. Carmichael, who was instrumental in securing support for establishing Rickenbacker Airfield in 1941, and leveraging the soon-to-be-built airfield to secure support for selection of Marietta for construction of Government Aircraft Plant 6 and the Bell Aircraft Corporation’s B-29 bomber plant. With his close ties to local business and political leaders, coupled with his business acumen and legal experience, he was subsequently hired as an attorney for the Bell Aircraft Corporation’s Georgia Division by Bell Aircraft’s president, Lawrence D. Bell, as was Rip Blair. In November 1944, still in his early 30’s, James Carmichael was elevated to general manager of the 28,000-employee plant when the original plant manager, Carl Cover, was killed in an aircraft crash.

In 1952, James Carmichael, turned over the general management of the plant to his assistant manager and successor, Daniel J. Haughton, an Alabama native who had risen into top management at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation’s headquarters in Burbank, California. It’s noteworthy that James Carmichael remained on the Lockheed board of directions until his death in 1972.

The Plant Re-Opens and the First B-29 Arrives from Texas

“The Incident, November 1951”

In November 1951, one plane crashed, ship 065: Joe Gabriel and Joe Sedita were the flight crew and both survived. The cause of the crash was the poor condition of the original engines on the stored B-29s. Several ship sets of engines were overhauled and then used as a rotable-pool on all future ferry-flights from Texas to Georgia, whereby the “good engines” would be installed on the aircraft before departing Texas, removed upon the aircraft arrivals in Georgia, then shipped back to Texas to be used again. There were no further catastrophic incidents.

The B-29s in Korea and the Arrival of The Jet Age

Lockheed’s Airlift Legacy – Beyond the B-29 Refurbishment Program

A Brief Introduction & Lockheed Aircraft Corporation’s History

The narrative, written content of this following section is, for the most part, heavily-quoted material from the New Georgia Encyclopedia and a few other sources, in some cases paraphrased or edited, but not my original material.

However, the layout and integration of the photo collection / time capsules is of my own design and effort, and what I suspect many who may find this material will find of most interest. This would likely be of more interest to readers who grew-up, lived or worked in and around Air Force Plant 6 and “The Bomber Plant” since the 1950’s when Lockheed Aircraft Corporation’s Georgia Division first came to Marietta, Georgia, to re-open Air Force Plant 6 and decided to find a way to keep it open and keep on producing aircraft for as long as they could.

So, here we are some 72-years later, and sure enough, the leadership at what is now the Lockheed Martin Aeronautics business area has stayed in Georgia and continues to develop, sell, produce, deliver and support both commercial and defense aerospace products and services, mostly underpinned by its highly successful C-130 Hercules production line at Air Force Plant 6 in Marietta, Georgia.

Only the Beechcraft Bonanza, which had its first flight in 1945, has been in production longer, but did have a break in production between 2020 and 2022, as none were produced in 2021. The other “grey beard” military aircraft include the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress heavy bomber which had its first flight in 1952, the last one being produced in 1962 with 52 of the original 744 built still operational and 18 in reserve as of 2022. The Northrop T-38 Talon trainer that first flew on 10 April 1959 and entered the USAF fleet on 17 March 1961, and the Lockheed U-2 Dragon Lady high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft that first flew on 1 May 1954 and 31 of the 104 U-2s built remain in service. A total of 841, Boeing 707-based KC-135s, C-135/7s, EC-137s, RC-135s and E-3s were built with many remaining in service.

Lockheed Martin may have gotten its feet on the ground in Georgia because of the B-29 refurbishment program in 1951, and to a certain extent the forthcoming Boeing B-47 Stratojet, licensed co-production program that was also on the table and a likely certainty when the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation re-opened the plant. However, those two programs would only provide a few years of production base through the mid-1950’s.

Interesting enough, the potential long-term production program opportunity presented itself on 2 February 1951 — just one month after the United States Air Force announced Lockheed would be re-opening Air Force Plant 6 — when the USAF issued a General Operating Requirement (GOR) and Request for Proposal (RFP) for a new transport to Boeing, Douglas, Fairchild, Lockheed, Martin, Chase Aircraft, North American, Northrop, and Airlifts Inc., noting Fairchild, North American, Martin, and Northrop declined to participate.

Lockheed would submit it’s proposal in April 1951 and win the development and two-prototype production contract with its Model L-206 airlifter design in July 1951, redesignated the YC-130 and the rest, as they say is history.

In September 1952, while the YC-130s prototypes were being designed and fabricated at the Lockheed California Division plant in Burbank Califorina, Georgia Division Vice President and General Manager, Dan Haughton, succeeded in making the business case to submit the C-130 full-scale development and production proposal based on doing the work at Air Force Plant 6 and the Lockheed Georgia Division’s plant in Marietta, Georgia.

In January 1953, the last of the 120 B-29’s refurbished by Lockheed’s Georgia Division in Marietta was delivered, and on 10 February 1953, the U.S. Air Force issued the first production contract for seven (7) C-130s, AF33(600)-22286), nearly a year-and-a-half prior to the YC-130’s first flight on 23 August 1954, followed immediately by the relocation of the program to Georgia, in parallel with the YC-130 prototype design and fabrication and flight test program development in California.

Lockheed’s California-Division finished designing and building the YC-130 “Hercules” prototypes, with first flight on 23 August 1954 and went on to exceed all of the USAFs stated performance requirements during flight testing and the rest, as they say, is history.

I’d created another blog/article entitled A C-130 Hercules History Trip that provides the full chronology of how the establishment of Rickenbacker Airfield and Government Aircraft Plant 6 was, in no small part, due to the efforts of James Carmichael and something of another image collection and time capsule regarding the initial C-130 move to Georgia and subsequent production history. However, I’ve since migrated all of that content into this document, and that history comes just a little later in this document.

But, in terms of the Lockheed Georgia Division legacy, every production C-130 Hercules airlifter — more than 2,600 delivered as of 2022 — has been produced in Marietta since 1954. While far-lower than it’s employment level at 28,145 in 1945, there are ~4,500 employees currently working at Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Marietta site, supporting work on the C-130J Super Hercules final assembly and the F-35 Lightning II center wing assembly production lines. With 3.4 million square feet of production space, the Lockheed legacy at Air Force Plant 6 will always include the C-130/L-100 Hercules, the L-329/C-140 JetStar, C-141 Starlifter, C-5 Galaxy and F-22 Raptor as all the production models were produced in Marietta.

Lockheed Employment Levels

However, it’s not all been sunshine and roses during these 72-years

Mind you, much of Lockheed’s later success in Marietta was achieved despite reaching and surviving near bankruptcy in the early 1970’s, driven mostly by the financially ill-fated, commercial L-1011 TriStar program at Lockkheed’s California Division. While the L-1011 was a highly successful program in terms of its technical achievement, it was woefully poor and ill-timed business failure that made the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation the first and the only business to apply for the Emergency Loan Guarantee Act of 1971 to rescue it from insolvency.

- Due to cost overruns, the number of orders needed to break-even on the L-1011 program had jumped from 300 to 500, at a time when they only had 244 orders and were also bleeding cash from the problem-plagued C-5 Galaxy airlift program. And, as if that weren’t bad enough, there were a series of bribery scandals that came to light do to the close attention and scrutiny Lockheed received associated with its government-backed loans.

- The investigation by the Security and Exchange Commission, hearings by Congress, findings and settlements led to the creation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act signed into law by President Carter back in 1977, in response to Lockheed’s use of what were deemed illegal payments associated with aircraft sales practices going back to the late 1950’s through the 1970’s.

- Although the urban legend lingers that taxpayers bailed-out Lockheed, that was not the case and, in fact, no taxpayer dollars were used. In reality, the fees paid by Lockheed and its banks to the Emergency Loan Guarantee Board for administering the loan program netted the government ~$30 million, which was sent to the U.S. Treasury.

- However, then-Lockheed chairman of the board Dan Haughton and vice chairman and president Carl Kotchian resigned from their posts on February 13, 1976 as a result of the scandal. However, Kotchian was adamant, “Lockheed was the scapegoat for over 300 companies the S.E.C. knew were involved in the very same practices… Some call it gratuities. Some call it questionable payments. Some call it extortion. Some call it grease. Some call it bribery. I look at these payments as necessary to sell a product. I never felt I was doing anything wrong.”

- According to Ben Rich, director of Lockheed’s Skunk Works: “Lockheed executives admitted paying millions in bribes over more than a decade to the Dutch, to key Japanese and West German politicians, to Italian officials and generals, and to other highly placed figures from Hong Kong to Saudi Arabia, in order to get them to buy our airplanes. Kelly [referring to Clarence “Kelly” Johnson] was so sickened by these revelations that he had almost quit, even though the top Lockheed management implicated in the scandal resigned in disgrace.”

- Coincidentally, it was in 1977 when the name Lockheed Aircraft Corporation was changed to just the Lockheed Corporation, to better reflect non-aviation activities of the company that dated back to 1954 when Lockheed formed a Missile Systems Division in Van Nuys, California, under the leadership of Lockheed Aircraft design team leader, Willis Hawkins.

The recently re-named Lockheed Corporation was also targeted and survived an attempted, corporate takeover in the 1980s, when leveraged buyout specialist Harold Simmons conducted a widely publicized, but unsuccessful takeover attempt, having gradually acquired almost 20 percent of its stock. It was believed Lockheed was attractive to Simmons because, at that time, Lockheed’s pension fund had a $1.4-billion surplus, which was his real target. Then Chairman and CEO Daniel M. Tellep and his board of directors were able to garner enough votes to retain control of the Corporation.

And, for better or worse, in the 1980’s Lockheed Corporation and the few remaining, large defense contractors, were put on notice by the Department of Defense that there were more contractors than future business available, to the point where major programs like the Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) Demonstration / Validation (Dem/Val) program essentially required the two companies who won the ATF Concept Development Investigation (CDI) program — Lockheed and Northrop — to form teams with other contractors, leading to the Lockheed-lead teaming arrangements with Boeing and General Dynamics and Northrop teaming with McDonnell Douglas, two aerospace defense contractors who merged in 1967.

Since then, Lockheed Corporation acquired Metier Management Systems in 1985, Sanders Associates in 1986, the General Dynamics Corporation’s Fort Worth Aircraft Division in 1993, and then merged with the Martin Marietta Corporation in 1995, after further consolidations were “encouraged” by the U.S. government. Some might argue that ,over time, much about Lockheed Martin Corporation has become more like the former Martin Marietta Corporation, and its Aeronautics busines area — the former, combined California and Georgia Divisions — more like the former General Dynamics Fort Worth Aircraft Division in terms of business practices and, to a certain extent, culture as well. Although, there remains some elements of the “old” Skunk Works and Georgia Division culture that had not totally vanished when I retired in 2018.

It’s worthy of note, McDonnell Douglas was merged-into Boeing in 1997 and, out on the west coast, Lockheed Corporation CEO Dan Tellep had already begun a major reorganization, closing the historic Burbank plant, the Rye Canyon Reserach & Development Facility in Valancia, California, the Ontario Air Services Company at the Ontario International Airport, and consolidating operations at Lockheed’s Plant 10 in Palmdale, California, on land adjacent to Air Force Plant 42 and leased from the Air Force next to the Palmdale Regional Airport.

- As a brief history, the 1930’s emergency U.S. Civil Aviation Administration (CAA) airstrip at Palmdale was bought and converted to the Palmdale Army Airfield in World War II. It was bought-back by the City of Palmdale as an airport after the war, then re-acquired by the U.S. Air Force in 1946 and became Plant 42.

- In early 1951, The U.S. Air Force put the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation on contract to develop a master plan for its new Air Force Plant 42, almost within a month of putting Lockheed Aircraft Corporation on contract to re-open Air Force Plant 6 in Georgia.

- In 1956, Lockheed leased what was designated as Air Force Plant 42’s Site 10 in its master plan, which it has since developed into its Plant 10 research, development, manufacturing, test and production facility, where the L-1011 TriStar production line was established in the 1980’s.

- Lockheed has also ocupied Sites 2 & 7 where the U-2, SR-71 and other operational overhaul and maintenance programs have been located.

The first photo at left is from the1953 after the 1930’s emergency CAA airstrip had become the Palmdale Army Airfield in World War II and had been acquired as a civil airfield, The 1980’s photo was taken when Lockheed was producing the L-1011 TriStar commercial passenger aircraft at what it called “Plant 10,” where Lockheed built building 601 — the L-1010 main production and assembly building clearly visible in the lower-left hand corner of the photo — and to the north, building 602, the L-1011 flight test center and hanger. The photo at right is how Plant 42 looks today with my best-guess at which firms are occupying or using which of the sites.

The Boeing Designed, Lockheed Georgia Division-Built B-47 Stratojets

During the 1950s, under now leased and operated by the Georgia Division of the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation under the leadership of James Carmichael and his vice president and assistant general manager, Daniel Houghton, Air Force Plant 6 saw a surge in production. Employment rose to 20,000 employees while Lockheed refurbished World War II vintage B-29Bs for the Korean conflict, and also produced 394 Boeing-designed B-47 Stratojets under license from Boeing. It was during this same period of time when the U.S. Navy relocated it’s U.S. Naval Reserve Station from Peachtree-DeKalb Airport, a move that required a runway expansion to 10,000′ to handle its U.S. Naval jet aircraft.

Other Resources:

- Aircraft Wiki @ Fandom: The Boeing B-47 Stratojet

- Aviation Geek Club: The Backbone of the Strategic Air Command in the Cold War

The Lockheed YC-130 / C-130 / L-100 Hercules Program

To the surprise of many people who don’t know the history of the C-130, the aircraft design and prototypes were both created by the Lockheed California Division’s “Skunk Works” using Skunk Works practices, and the two YC-130s were the only C-130s not produced in Georgia. However, Lockheed was able to successfully stand-up the full-scale production program across country at its fledgling Georgia Division where, to date, over 2,600 C-130s, including over 500 of the latest C-130J-models have been produced and delivered, and over the 67 years it’s been in production, has operated out of over 70 different nations at one time or another.

“I think the concept was good, it demonstrated our ability to hand it off to another production organization who took it and made it work.” Clarence L. “Kelly” Johnson

The YC-130 Program Chronology

On 2 February 1951, the United States Air Force issued a General Operating Requirement (GOR) and Request for Proposal (RFP) for a new transport to Boeing, Douglas, Fairchild, Lockheed, Martin, Chase Aircraft, North American, Northrop, and Airlifts Inc., noting Fairchild, North American, Martin, and Northrop declined to participate. The purpose was to develop a new tactical airlifter to replace the recently developed and still in-production Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar that was already proving to be inadequate for the evolving, larger and heavier U.S. military needs in the early stages of the Korean conflict. Proposals were due by April and oversight of the Lockheed proposal effort was assigned to Willis Hawkins, who managed Lockheed’s preliminary design department at the Lockheed Aircraft Company and its Skunk Works in Burbank, California.

In April 1951, the five competing companies submitted a total of ten designs: Lockheed two, Boeing one, Chase three, Douglas three, and Airlifts Inc. one. Lockheed responded to the 7-page request for proposal with a 130-page document for what was at the time the Lockheed model L-206-1, later changed to model L-82. Lockheed also submitted a second model L-206-2 design that looked similar to the L-206-1, but with a smaller wing area.

Note: There was a third L-206-3 design that evaluated the feasibility of a packet-aircraft concept that was not submitted. If Kelly Johnson thought the L-206-1’s design was un-Lockheed and ungainly, I can only imagine what he thought of the L-206-3. I’ve since seen independent confirmation of the existence of the L-206-3 concept, which was greatly appreciated.

On 2 July 1951, Lockheed was selected to move forward with its L-206-1 design and build two prototypes, based on a 2-month long evaluation by the Air Force, where its closest competition had been the four-engine turbo-prop design submitted by Douglas Aircraft.

On 11 July 1951, Lockheed was awarded contract AF 33 (038)30453 calling for the construction and flight testing of two prototypes of what had been designated as the YC-130 and was eventually given the name “Hercules” based on an employee competition to come up with a name following the contract award.

In September 1952, Georgia Division Vice President and General Manager, Dan Haughton, succeeded in making the business case to propose and establish the full-scale development and production program at Air Force Plant 6 and the Lockheed Georgia Division’s plant in Marietta, Georgia.

- The rationale was sound, as production lines for Lockheed’s T-33 Shooting Star jet trainers, C-121 and commercial Constellation airliners, as well as the P-2 Neptune maritime patrol and anti-submarine aircraft were already running at capacity and the Lockheed California Division’s Burbank plant did not have the additional capacity to support C-130 full-scale production program.

- Lockheed had just re-opened Air Force Plant 6 in January for the short-term refurbishment of 120 Boeing B-29s and licensed, co-production production of the Boeing B-47 Stratojet. However, after cleaning-up then establishing the B-29 and B-47 production lines, Air Force Plant 6 clearly had the additional capacity required for a C-130 production line.

- A widely-needed, tactical transport with an international export market would potentially give the Georgia Division at Air Force Plant 6 a longer production horizon in Marietta, an underlying goal of Carmichael when they agreed to re-open the plant. It was a vision that was shared by Haughton, who was an influential and rising star at Lockheed and would become Chairman and CEO in 1967.

In October 1952, Lockheed announced its decision to establish the C-130 full-scale production program at the Georgia Division in Marietta, with Al Brown as the program Manager.

- Brown moved temporarily from Marietta to Burbank and along with a team of Georgia Division engineers who worked side-by-side with the California Division during the prototype design, manufacturing and assembly process.

- At the same time, the portions of California Division’s design team were temporarily moved to Marietta to oversee and work with the Georgia Division on the production proposal. The combined design team made a few changes to reduce the unit cost of the C-130, but the visual difference between the prototypes and first production articles was not noticeable.

- Note: Willis Hawkins — the man credited with the design of the C-130 — during an interview regarding the C-130 program recalled how most of California Division personnel sent to Georgia, “…went kicking and screaming, because they didn’t want to have anything to do with Georgia. Two years later, we tried to bring them back to California and they were kicking and screaming again because they liked Georgia so much that they didn’t want to come back.”

On 10 February 1953, the USAF issued the first production contract for seven (7) C-130s, AF33(600)-22286), nearly a year-and-a-half prior to the YC-130’s first flight on 23 August 1954.

During 1953, the C-130 personnel moves continued and asset transfers from the California to the Georgia Division began, to include the move of the 50-ton, wood and metal full-scale C-130 mock-up. The massive mock-up was placed on a U.S. Army barge and had to pass through the Panama Canal on its way from the port at Long Beach, California, to the port at Savannah, Georgia, and be trucked 270-miles to Air Force Plant 6 in Marietta.

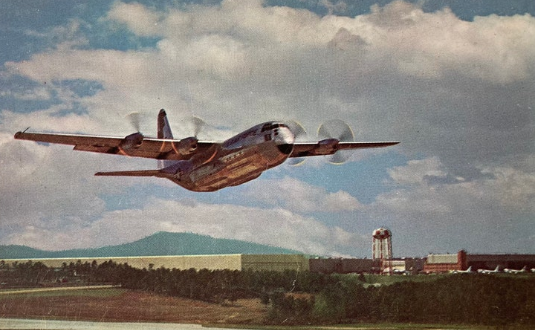

On 23 August 1954, the second YC-130, LAC 1002 and USAF SN 53-3397, successfully completed its first flight, an hour-long flight from the Lockheed plant adjacent to the Burbank Airport to the Air Force Flight Test Station at Edwards Air Force Base, California, 51 miles north-northeast of Burbank, with a Lockheed-built PV-2 Neptune flying chase and Kelly Johnson aboard, now an advocate for the C-130 design.

- Pilots Stan Beltz and Roy Wimmer reported good handling characteristics and considerably better-than-expected performance. The latter was due in part to the basic guaranteed mission weight of 108,000lbs having been reduced by 5,000lbs, allowing cruising speed to be ~20% higher, takeoff distances to be ~25% lower, ceiling and initial climb rates to be ~35% higher, landing distances ~40% shorter, and single-engine-out climb rates were a stunning 55% higher than predicted.

- The first YC-130 built, LAC 1001, SN 53-3996, was initially used for structural ground tests and did not achieve its first flight until 21 January 1955.

In 1954, and shortly after the successful first flight, the Air Force increased its C-130 production order from seven to 75 airplanes.

Interesting Developments: Full-Scale Models & Hydrostatic Testing

The lower row of photos includes an illustration of the water tank erected near B-4 for hydrostatic testing of a full-scale production fuselage and center wing box, and then the man-made basin that was built to support hydrostatic testing of the empennage and other major components, which still sits near side South Cobb Drive.

The First Articles & First Flights

The First Lady & Fire on Number 2

The lower row of images illustrate how, like the mythological Phoenix that rose from ashes, “The First Lady” C-130A 53-3129 received a new center and outer wings and was cycled back into production during 1956, being delivered to the USAF in 1958 where it supported test operations. In 1968, the first AC-130A conversion prototype was flown by Raytheon, and 53-3129 was one of the first 10 C-130A’s to receive the modification. It went on to serve another 27-years until it was retired to the Air Force Armament Museum at Elgin, AFB, FL, in 1995 where it sits today

The C-130A Is No Trash Hauler

The photo at right is of the “Four Horsemen” C-130A Aerial Demonstation Team based at Stuart AFB, Tennessee. Yes, there was such a unit, and you can read more about them here. You can also find a Lockheed-produced video from the 1950’s here.

A Plane for All Reasons & Missions

Moving from the upper right to left, once again the U.S. Navy was a C-130 operator from early-on and fielded the EC-130Q electronic combat variant to support the TACAMO (“Take Charge and Move Out”) mission. The TACAMOs provided airborne Very Low Frequency (VLF) communications to the U.S. submarine fleet via a long, trailing antenna that could be deployed and recovered during flight. Above center is a USAF C-130J-30 with the MAFFS fire-retardant dispersal system supporting wildfire suppressionmissions, and at right is a Drone Control C-130 (DC) used to launch target and other drones used by the U.S. military.

At the lower left is a U.S. Navy KC-130F that was used to demonstrate carrier operations in Octover and November 1963 by successfully landing and taking off from the U.S. Forrestal: KC-130F BuNo 149798, loaned to the U.S. Naval Air Test Center, made 29 touch-and-go landings, 21 unarrested full-stop landings and 21 unassisted take-offs on Forrestal at a number of different weights.. In the middle is an HC-130H fitted with the Fulton airborne recovery system (aka, skyhook) used for various types of special missions.

The L-100 Commercial Variants

The C-130J Variants in Production

The C-130J model was developed in the early 1990s and achieved first flight on 5 April 1996. Rather than including a lengthy section on the development program, I’ve decided to include several links to excellent on-line resources for those interested in learning more.

- Wikipedia’s Entry on the C-130J Super Hercules

- Avionics Modernization and the C-130J Software Factory

- POGO Article & Criticisms of the C-130J Program

- The Military Analyzer Looks at the C-130J

As as June 2022, over 500 C-130Js have been built and delivered since 1999, making it one of the most widely-used, military airlifters. Despite being a nearly 30-year old redesign of the 71-year-old original, the C-130 continues to perform a wide variety of missions and high-levels of inter-operability by the nearly 50 nations with C-130s or L-100s, of which 16 operate the C-130J.

As of June 2022, the USAF active-duty, reserves and guard units have the largest C-130 fleet with 279 airframes, of which 163 are C-130J models, but plans to reduce that number to 255 in the near term. It’s important to note, C-130J-30 long-body models are being procured to replace national guard operated, older C-130H “short-body” models which will likely account for the ability to make those planned reductions in airframes without a significant reduction in airlift capability, given the vastly increased payload and performance of the C-130J models.

The Embraer C-390 Millennium, The First Serious Alternative

The two-engine, turbofan powered Embraer C-390 on which development began in 2009 with the first flight on 3 February 2015. It also received Brazilian civil type certification on 23 October 2018. It was developed to provide an modern alternative to the four-engine, turboprop C-130, targeting nations with smaller fleets of aging, older-model C-130s or Russian-produced medium cargo aircraft. At present, Embraer has sold aircraft to its home country and launch customer Brazil, as well as Portugal, Hungary and most-recently the C-390 was selected over the C-130J by the Netherlands. A total of eight (8) C-390s have been produced to date, with the first customer delivery to Brazil in 2019 who, as of June 2022, has five (5) of the aircraft in service.

Other Resources:

- Aircraft Wiki @ Fandom: The Lockheed C-130 Hercules

- The Lockheed L-100: Why & When Delta Flew the Plane

The Lockheed Skunk Works Designed, Georgia Built L-329 / C-140 JetStar Business Jet

In something of a reprisal of the C-130 program model, in the 1950’s Kelly Johnson’s Skunk Works decided to create the business jet market with a cutting-edge, Lockheed Skunk Work’s design: the CL-329 JetStar, the first business jet.

What’s amazing, and perhaps says a lot about Kelly Johnson’s drive, determination and leadership, is that the new project was started while the Lockheed-California Division was already in the midst of running production lines for the T-33 Shooting Star jet trainers, C-121 and commercial Constellation airliners, as well as the P-2 Neptune maritime patrol and anti-submarine aircraft, while also developing the L-1649 Starliner airliner (the final version of the Constellation), L-188 Electra airliner, U-2 Dragon Lady high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, and F-104 Starfighter interceptor. Ben Rich’s book, Skunk Works, captures a lot about Kelly Johnson’s influence and personality in his book that’s well worth a read: I worked with a lot of the amazing people mentioned in the book at Lockheed over the years, and all of them were quite humble with regard to their work and accomplishments, but all were brilliant, focused and committed.

Development of the L-329 JetStar

Like the L-206 / C-130 Hercules, the aircraft was designed by the Lockheed California-Division’s Skunk Works using a Skunk Works design team and practices in Burbank, California. Two-prototypes were built and had first flights that began at the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation-owned, Burbank-Hollywood Airport and ended 51-miles away at the Edwards Air Force Base test center.

The following are extracts from an excellent article on the UTX and UCX Programs that ultimately led to the development and production of both the Lockheed JetStar and the North American Saberliner.

In 1956, the US Air Force (USAF) issued a “general design specification (GDS)” for two light jet transports, including a twin-engine machine with four passenger seats, for the training / utility role, designated the ” Utility-Trainer Experimental (UTX)”; and a larger, four-engine light airliner / utility transport, the “Utility-Cargo Experimental (UCX)”. The GDS was not really a request for proposals, in anticipation of a contract award; the Air Force it had no money to issue a development contract, and any companies working on the UTX or UCX would have to do it on company funds. The most that could be said, if not really promised, by the USAF was that the service would be interested in buying a quantity of aircraft in both categories if companies developed them on their own funds — suggesting a buy of 1,500 UTX and 300 UCX aircraft.

The quantities were tempting, the lack of commitment discouraging. However, US aviation companies had been interested in developing a light jetliner for the civil market anyway, and the UTX-UCX requirement was more or less just a prod in the right direction.

Utility-Cargo Experimental (UCX) Program:

The Lockheed Company decided to move ahead on a design for the UCX specification. The program was under the general direction of Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, Lockheed’s chief designer. The first of two prototypes of the “L-329 Jetstar” performed its initial flight on 4 September 1957, with test pilot Ray Goudey at the controls. The Jetstar was a sleek aircraft, of all-metal construction, with low-mounted swept wings, tricycle landing gear, and turbojet engines mounted on each side of the rear fuselage. It was a configuration that would become all but universal for executive jets.

The McDonnell Aircraft Company also developed a small four-jet airliner for the UCX specification, the “McDonnell 119”; when the UCX effort faded out, the company tried to push the design for commercial service as the “Model 220.” The Model 220 looked like a “baby” version of a 707 or DC-8 jetliner, with low-mounted swept wings and its four engines — Westinghouse J34-WE-22 turbojets with 13.3 kN (1,350 kgp / 2,980 lbf) thrust each — on individual pylons under each wing. It could carry two pilots, a flight attendant, and ten passengers in luxury accommodations; or it could carry 26 passengers in a high-density configuration.

Utility-Trainer Experimental (UTX)

When the USAF came up with the UCX-UTX specification in 1956, the North American Aviation company decided to pursue the smaller UTX trainer, having been working on concepts for a small twinjet transport aircraft from 1952. Even if the UTX business didn’t amount to much, North American still felt their small twinjet had potential in the civil market. The initial prototype — the “NA-265” — performed it maiden flight on 16 September 1958, with test pilots J.O. Roberts and Gage Mace at the controls. It was called the “Sabreliner”, because it leveraged off the design of the flight surfaces for the North American F-86 Sabre fighter. Since no other companies chose to compete for the UTX, NAA won the contest by default.

The UCX & UTX Programs Go Nowhere….

The original UTX/UCX programs fizzled, but both the Lockheed L-1329 JetStar which was provisionally chosen over the McDonnell 119/220 (only 1 ever built) for the UTC program and the North American Saberliner, the only offering for the UTX program ended-up being procured to meet other restated requirements.

The Lockheed Jetstar I

Of the 300 aircraft envisioned by the Air Force for the UCX, the USAF only bought sixteen Jetstar I’s, in two variants:

- C-140A: Five Jetstars for the Air Force Communications Service, being equipped to test and calibrate airport navigation aids. They went into service in 1962, and served to the early 1990s.

- VC-140B: Eleven Jetstars as liaison / VIP transports, flown by the Military Airlift Command as part of the presidential flight, carrying high-ranking government officials. They were actually among the first Jetstars to be delivered, in 1961, with five actually obtained as near-stock “C-140Bs”, and then promptly upgraded to VC-140B spec.

- The US Navy also ordered two “C-140C” Jetstars, but the order was canceled; the Air Force also considered a trainer version of the Jetstar, the “T-40”, but it didn’t happen.

- The Jetstar was obtained by a number of foreign military services, including Germany, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia, for use in liaison, utility, and VIP transport roles. The Jetstar was said to have carried an unusual number of heads of state. One was used by the US National Aeronautics & Space Administration as a testbed aircraft, in one instance with an experimental turboprop engine on a pylon mounted on the back.